100 Days of Belarusian Rule of Law – Analysis by Libereco

100 Days of Belarusian Rule of Law

Political practice and human rights violations in Belarus after the EU lifted its sanctions

(Period examined: 15 February to 24 May 2016)

Introduction

Belarus has its own perception of human rights, states President Aliaksandr Lukashenka; suggesting its discordance with that of the EU. He argues that he does not object to the EU having its own understanding: “The European Union is a mature organization with smart people who can formulate what they want.”1 And therefore, claims neither party should interfere with the others’ perceptions. This attitude seems to be mutual, with the EU evidently deciding to turn a blind eye on human rights violations in Belarus.

On 15 February 2016, the EU Foreign Affairs Council suggested lifting sanctions against three companies and 170 individuals from Belarus, and then ten days later, the Council of the European Union inaugurated the proposal. This is a benchmark in the political rehabilitation of Belarus which has been ongoing since mid-2014, when the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine escalated. This parallelism is not a coincidence; in face of the crisis in Ukraine and the deteriorating relationship with Russia, the EU needs a stable partner on its Eastern borders. Lukashenka´s hosting of the peace talks on Ukraine in 2014 and 2015 illustrates that the EU views Belarus as a promising candidate. As the country is currently demonstrating the will to cooperate and is pretending to loosen its authoritarian reins, the EU is seemingly happy to commit.

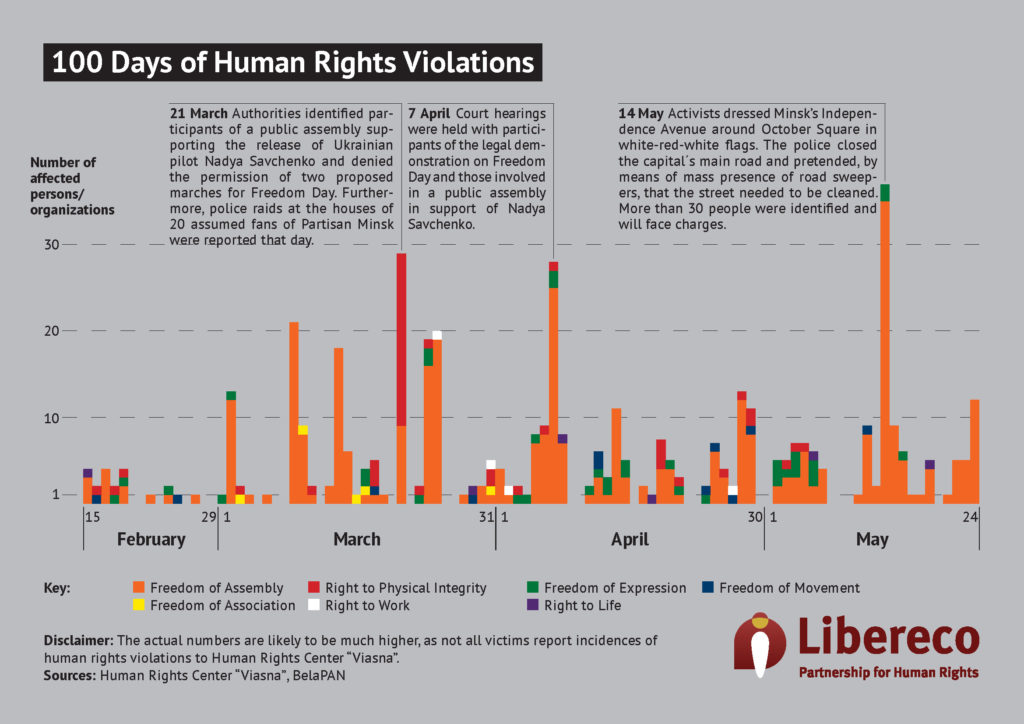

In face of the recurrent human rights violations, Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights decided to investigate whether indeed a political liberalisation can be discerned and how it manifests itself. Through the means of human rights center Viasna´s monitoring, Belapan´s coverage and other publicly available sources, we examined 100 days of Belarusian rule of law. Starting on the day the EU decided to abolish the sanctions, we analysed political, executive and legal practice focusing on human rights violations. The findings show that the situation of human rights in Belarus has not improved at all, and in some respects it has even deteriorated. Punishments and harassments however, have been kept beneath the level which would attract international attention.

A brief history of the sanctions

In the past decade, imposing and lifting sanctions has been a commonly used instrument of the EU’s foreign policy towards Belarus and other countries. The measures have included travel bans, freezing of assets, an embargo on arms including related material, and an exports ban regarding equipment suitable for internal repression. In 2004,2 in response to the disappearance of four opposition-affiliated Belarusian citizens in 1999 and 2000 and the authorities´ failure to investigate the matter, the EU placed its first sanctions on Belarus.3 The restrictions were supposed to exert pressure on Belarus to make the state implement international human rights standards, abolish the death penalty and respect its own constitutional rights. The Belarusian constitution guarantees the right to freedom of thoughts and free expression, as well as freedom of assembly and association (art. 33, 35 and 36).4 As a UN member, Belarus has ratified and is therefore obliged to implement the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The EU regularly amended the sanctions in reaction to developments in Belarus. After the 2006 and 2010 presidential elections, the travel bans were expanded to include those responsible in falsifying the votes, as well as those involved in the violent dispersal of the peaceful protestors who had subsequently questioned the election outcomes. In 2006, Lukashenka himself was banned from travelling to EU countries and his private assets were frozen. Whenever the regime showed slight traces of the desired improvements in the field of democracy and human rights, the EU responded by partly suspending the sanctions. In this way Lukashenka’s travel ban ended in 2008.

After Belarusian authorities violently cracked down on a large protest-rally, following the presidential elections of 2010, and arrested approximately 700 activists, including seven oppositional presidential candidates, the EU-Belarus-relationship hit rock bottom. Following these events, the EU´s restrictive measures reached a peak with 243 individuals and 32 companies listed.5 Lukashenka’s ban and asset freeze were reintroduced and upheld until August 2014.

Since the last presidential election in October 2015, Western voices positively emphasized that the Belarusian authorities refrained from mass arrests like in 2010 – omitting the fact that due to the absence of considerable protests there was no “need” of mass repression at this time. Even though the International Election Observation Mission detected “significant problems, particularly during the counting and tabulation” which “undermined the integrity of the election”6 , and EU Vice-President Federica Mogherini and Commissioner Johannes Hahn underlined that “Belarus still has a considerable way to go towards fulfilling its OSCE commitments for democratic elections”7 , the “peaceful” elections were presented as a sign of liberalization. Together with the release of all political prisoners in August 2015, they paved the ground for a significant improvement of EU-Belarus relations.8

Accordingly, the EU temporarily suspended the asset freeze and travel bans applying to the above mentioned 170 individuals and three companies, right after the elections.9 On 25 February 2016, the Council of the European Union almost fully abandoned the restrictions.10 The only sanctions which stayed in place are those directed against the persons suspected to be directly involved in the aforementioned disappearances of four people in 1999 and 2000.11

100 days after the lifting of the sanctions… … use of death penalty increased

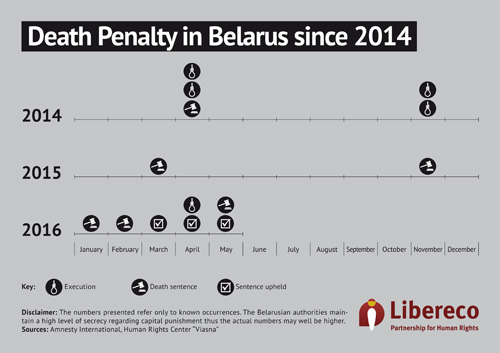

On the same day that the EU Foreign Affairs Council initiated to lift the sanctions, the Minsk regional court sentenced the 31-year old Siarhei Khmialeuski to death. Belarus remains the only European country that upholds and carries out capital punishment. Only five weeks passed until the Homel Regional Court handed out the next death sentence, already the third in 2016. As all convicts´ appeals were denied, their only chance of survival is a presidential pardon, which is highly unlikely. During his 22 years in office, Lukashenka has pardoned only one person, whereas at least 250 death sentences have been issued since 1994.

In fact, with two death sentences, three denied appeals and at least one execution, the use of capital punishment in the investigated 100 days since the sanctions were lifted, already outnumbered that in the whole year of 2015.

On Monday, 18 April 2016, after sunset, the state’s executioner killed death row prisoner Siarhei Ivanou with a shot in the back of his head. At least four prisoners are still on death row and we do not know whether they are alive or already executed. Indeed, it is notoriously difficult to obtain information about capital punishment. Court cases are held behind closed doors, with proceedings around the punishment and the numbers regarding the amount of sentences and executions being kept secret. The execution dates are not disclosed, not even to the death row prisoner or his family. Convicts live in constant fear of execution and have no opportunity to say goodbye to their families and friends. The punishment extends to the family, who after receiving no notification of the execution, are also withheld information regarding the burial place. An example of this being, Siarhei Ivanou, whose family only found out about his execution when they tried to visit him in prison – two weeks after his death.

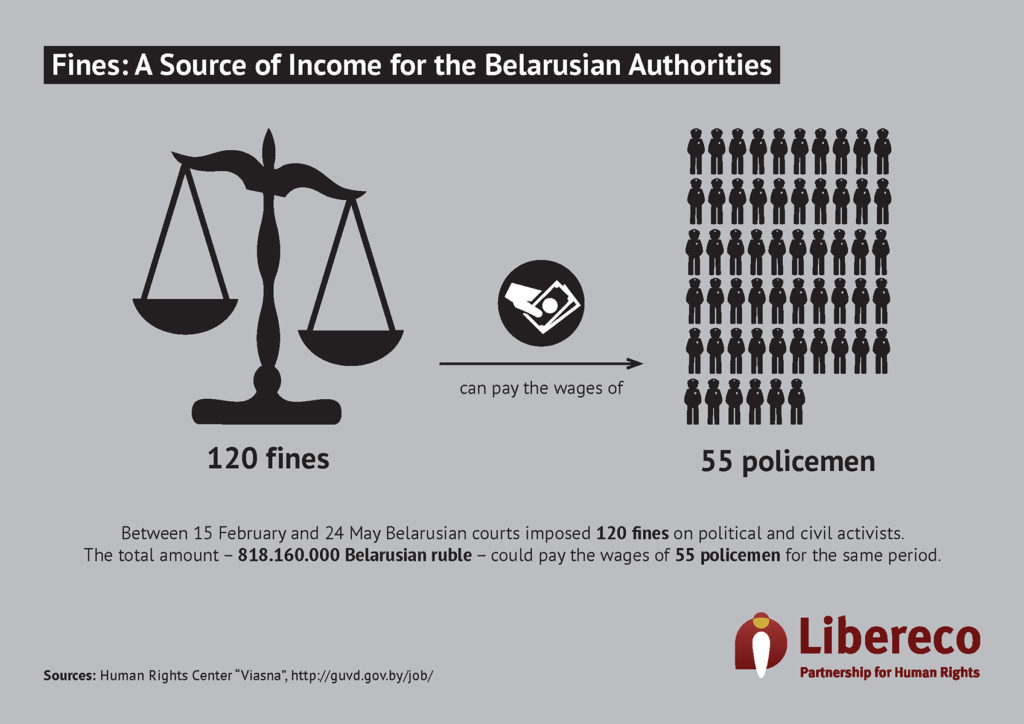

… fines for public assemblies skyrocketed

Throughout the whole investigation period the Belarusian state restricted the right to peaceful assembly – no matter whether the gathering served to protest the high costs of medical care, to improve the situation of small-scale entrepreneurs, or to raise attention for ecological issues. Most often the authorities justified their decisions by referring to article 23.34 of the Belarusian Administrative Code. This article obligates the organizers of a public assembly to ensure that doctors and police are on stand-by, and that subsequent cleaning of the site will take place, meaning that they have to pay for police, medical and communal services themselves – a practice unparalleled in Europe. This undermines art. 35 of the Belarusian constitution, which states that “the freedom to hold assemblies, meetings, street marches, demonstrations and pickets that do not disturb law and order or violate the rights of other citizens of the Republic of Belarus, shall be guaranteed by the State”.

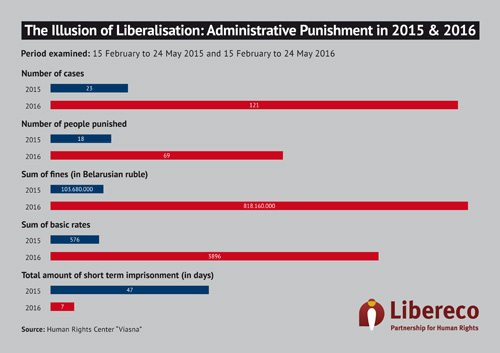

Participants of public assemblies held without permission faced administrative charges, usually in the form of heavy fines. During the investigation period, the authorities gave out over 120 fines earning over 818 million BYR – more than 37.000 Euro. The fines from the past 100 days thereby equates to the wages of 55 policemen for the same period.12

During the same period in 2015, authorities imposed only 19 fines, worth altogether 103,68 million BYR. The handing out of fines has sextupled. The alternative form of administrative punishment – the short prison sentence – has decreased accordingly. While four people received a total of 47 days in prison during this time period in 2015, only one person faced 7 days during the investigated period in 2016. Hence, repressions are not decreasing but simply taking another form – fines – which are much less likely to be reported in international media.

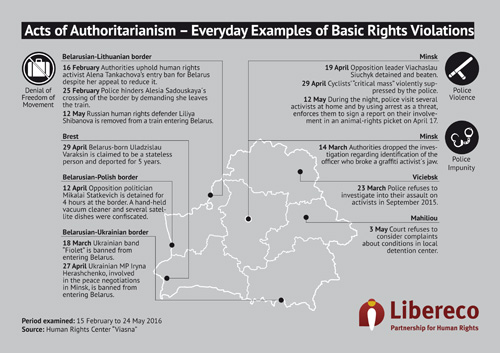

Even in the rare cases of permitted public protests, demonstrators and potential participants are not safe from fines. Security personnel stopped and searched Natalia Samatyya in the metro on her way to the authorized Chernobyl commemoration march. When they found a self-made poster she was taken into custody. Despite her serious medical condition she was kept in a police station cell until the next morning and she will now face administrative charges.

The case of Uladzimir Matskevich points to a similar arbitrary approach; he was tried for participating in a demonstration he did not attend. Policemen testified that they had seen him, whereas he could prove, by means of stamps in his passport, that he was not even in the country during the protest – a clear demonstration of the lack of reliability in police statements. Despite this obvious reason for closing the case, the judge decided to send it back for revision – which displays a lack of rule of law.

When imposed fines are not paid, bailiffs confiscate possessions. Disregarding Belarusian law they take even equipment necessary for work – as happened for instance in the case of the taxi driver Leanid Kulakou.

… freedom of speech remained severely limited

The availability of free information in Belarus is still limited by the strict control on media and repression against independent journalists. During the investigation period, the journalist Kastus Zhukouski was fined 3 times for “illicit manufacturing of media products” with a total amount of 31,5 million BYR, about 1440 Euro – roughly the amount an average freelance journalist earns in 100 days.

However, it is not just the media which is affected by the limited freedom of speech. Human rights organizations have demanded to decriminalize defamation offenses by abolition of the articles of the Criminal Code of Belarus regarding for instance “defamation of the president of the Republic of Belarus” (art. 367), “insulting the president“ (art. 368), “insulting the authorities” (art. 369), “insulting judges and lay judges” (391), “discrediting the Republic of Belarus ” (art. 369-1). Nevertheless, the articles, which carry several years of imprisonment for violation, are still in place and applied. An exceptionally poignant example of the effects of these laws is the case of the 80-year old Aliaksandr Lapitski, who was found guilty of three of these apparently socially dangerous acts at once (art. 368, 369, 391). He was sentenced to (involuntary) hospitalization and compulsory psychiatric treatment.

… freedom of association arbitrarily denied

Since the lifting of EU sanctions, the Belarusian authorities have not changed their selectivity in the registration of organizations. Among the turned down applications was the public association “For Statehood and Independence!” whose activists include Nobel Prize winner Sviatlana Aleksievich and former Belarusian president Stanislau Shushkevich. The public association “For Fair Elections” was denied registration for the 4th time and the Belarusian Christian Democrats for the 6th time. Most often, the authorities substantiate their denial with complaints regarding the formal process. They objected for instance, that the information in the list of founders was incomplete, because it lacked work telephone numbers or the correct name of the work place. In the case of the Christian Democrats, allegedly a number of listed party co-founders were not affiliated with the party at all. According to legal experts the denials were not according to permissible restrictions on freedom of association as provided by Part 3 Art.5 of the Belarusian constitution and Art. 22 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

… police violence and harassment during detention are still the norm

On 29 April, police riot squads violently cracked down on a “critical mass” – a peaceful cyclists’ protest event, as is common all over the world – in this case against the building of a nuclear power plant. The investigation period also saw the first violent arrest in Belarus in months, when on 19 April 3 a.m. police officers arrested and physically assaulted Viachaslau Siuchyk, leader of the movement Razam. These and other cases show that the Belarusian police force still applies arbitrary violence against peaceful protesters, as well as during the detainment of people.

As a rule, the police are not held accountable for the violence inflicted on demonstrators and those arrested. Impunity reigns as complaints are routinely turned down by the court. On 21 March for instance, Viachaslau Kasinerau who was severely assaulted whilst detained for spraying graffiti last summer, was notified that the investigation into his beating was suspended as investigators were unable to establish the person who broke his jaw among those on duty. It is even common practice to charge the victims for hooliganism after a violent arrest. On 30 January, a public protest against police violence resulted only in high fines for the participants.

Apart from physical violence, the police also exerts more subtle forms of repression. House searches and surveillance clearly serve more goals than securing evidence alone, with police turning up without a warrant and often doing so in the middle of the night. Also the questioning of suspects is used for more than just legal proceedings. Baranavichy entrepreneur Mikalai Charnavus was repeatedly called in for questioning at the same time that a demonstration was held he might otherwise have participated in.

Being sent to prison would seem sufficient as a punishment, but harassment often does not stop there. Inmates of Belarusian prisons and penal colonies regularly face additional punishments. Human rights defender Andrei Bandarenka was separated from his fellow prisoners, allegedly for writing too many letters, but more probably for helping others to write complaints. Aliaxei Khmialeuski was denied transferal to a lighter regime after his brother received a death sentence in February.

After the release of all political prisoners in 2015, the subsequent and politically motivated detention of activist Mikhail Zhamchuzhny reintroduced political imprisonment in Belarus. Human rights organizations have repeatedly called for a revision of the sentence and a fair trial for the convict – so far without any response. Moreover, the authorities have failed to rehabilitate the released political prisoners and fully restore their rights. Neither did they close politically motivated criminal cases which were initiated in previous years, as for example the criminal investigation against the former presidential candidate Ales Mikhalevich, accused for participation in “riots” on 19 December 2010.

… Belarus remains far removed from rule of law and respect for human rights

Even though the number of arrests, detentions and new politically motivated criminal cases has decreased since the mass release of political prisoners in August 2015, the assessment of 100 days since the lifting of the sanctions shows that the country is still far from approaching democracy and rule of law. The few improvements are fragile as they are a matter of everyday policy, and not of legislation.

Continuous harassments show that Belarusian society is facing more rather than less pressure, although this pressure is less visible than before. Less publicity-provoking measures, such as fines, replaced the obvious repression of political imprisonment and the violent breaking up of demonstrations that made international headlines before. Below the surface however, fines are sky-rocketing both in amount and frequency compared to the same period a year before. Behind closed doors, more people have already been sent to death row and executed than in the whole of 2015.

The Belarusian authorities may seemingly have created a less repressive and more internationally acceptable image, but the figures tell another story. Violations against basic rights such as freedom of assembly, association, free speech and the right to life still occur on a daily basis in Belarus and have changed in form but certainly not in frequency. The EU might have its reasons for improving its ties with the state of Belarus, but the reasoning that it has turned a path towards democracy and human rights does not stand true.

Research and authorship:

Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights was established in 2009 and is based in Germany and Switzerland. The organization campaigns for human and civil rights in Belarus and Ukraine.

Belarusian human rights center Viasna was established in 1996 and remains one of the most important independent human rights organizations of Belarus. Since its registration was withdrawn by the authorities in 2003 it is forced to operate on the verges of legality.

Published on 2 June 2016

Infographics and notes:

Notes:

- http://eng.belta.by/president/view/belarus-president-meets-with-eu-representative-on-human-rights-89506-2016/

- http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004E0661&from=EN

- The extensive Pourgourides Report states that “steps were taken at the highest level of the [Belarusian] State actively to cover up the true background of the disappearances, and to suspect that senior officials of the State may themselves be involved in these disappearances.” See: http://www.refworld.org/pdfid/4162a4654.pdf#7 2

- http://law.by/main.aspx?guid=3871&p0=V19402875e

- http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:285:0001:0052:EN:PDF

- http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/belarus/191586?download=true#1

- http://eeas.europa.eu/statements-eeas/2015/151012_04_en.htm

- http://eeas.europa.eu/factsheets/docs/eu-belarus_factsheet_en.pdf#1

- http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2015/10/29-belarus/

- The relevant legal acts were adopted on 25 February 2016, following a political decision taken by the Council on 15 February 2016. See http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/02/25-belarus-sanctions/

- They target the former ministers of Interior, Uladzimir Navumou and Yuri Sivakou, the former Prosecutor General and Head of the Presidential Administration, Viktar Sheiman, and the commander of the Interior Ministry´s Special Forces, Dzmitry Paulichenko. See: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016D0280& qid=1464175250703&from=EN#3

- http://guvd.gov.by/job/

Disclaimer/Funding: This publication and its research was done by members of Libereco and Viasna who contributed voluntarily. We did not receive any financial support by third parties. If you want to support our work for respect for civil and political human rights in Belarus, you can donate to the following accounts or via Paypal (send to: paypal@lphr.org):

Donations account Germany: Account holder: Libereco Reference: Belarus IBAN: DE96 8309 4495 0003 3203 32 BIC: GENO DE F1 ETK

Donations account Switzerland: Account holder: Libereco Reference: Belarus Post Account: 85-792427-8 IBAN: CH61 0900 0000 8579 2427 8 BIC: POFI CH BE XXX

Any donation paid to Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights are tax deductible in Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. You will always receive a donation receipt from Libereco in February of the year after your donation.